In the aftermath of the earthquake, a Haitian man with an enormously swollen leg and several sites of infected skin breakdown presented to the Hôpital Sacré Coeur trauma center. Was this a case of crush injury or massive blood clot? Actually this was a case of lymphatic filariasis – one of the so called “neglected tropical diseases” still endemic to Haiti.

Lymphatic filariasis is a mosquito borne parasitic disease which in its final stages can result in grotesque enlargement of a limb (“elephantiasis.”)

In 2001, blood samples were collected from Haitian school children aged 6-11 years1. The overall prevalence of lymphatic filariasis was 7.3%. Infection was identified throughout the country (87.9% of communes). The most heavily infected areas were concentrated in the northern part of the country.

In 2008, the Carter center launched an initiative to eliminate lymphatic filariasis from both Haiti and Dominican Republic. This was based on an expert opinion statement in 2006 that such a goal was technically feasible.

In 2008, the Carter center launched an initiative to eliminate lymphatic filariasis from both Haiti and Dominican Republic. This was based on an expert opinion statement in 2006 that such a goal was technically feasible.

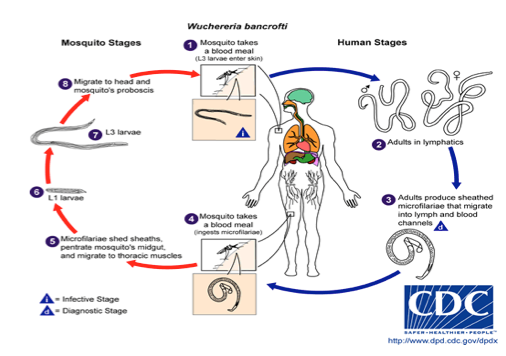

The Culex mosquito is the major vector for lymphatic filariasis in Haiti. The major pathogen is W. bancrofti. Based on the 2001 survey mentioned earlier, risk factors for the disease include agricultural vegetation and an altitude of less than 70 meters. Others have suggested that sugar cane cultivation may result in increased risk of infection as these areas provide suitable habitats for the Culex mosquito.

The life cycle for this parasite is as follows:

Mosquitoes inject larva into the skin. The larva travels through the lymphatic system and ultimately takes up residence near lymph nodes as adults. Adult worms then mate to produce thousands of infectious microfilariae per day. These microafilariae are taken up by mosquitoes during a blood meal. The microfilaria produces no symptoms. Most symptoms are caused by obstruction to lymph flow from the adult worms. Lymph flow obstruction correlates with the adult worm burden which requires many years to become significant. Thus, lymphatic filariasis is a disease that begins in childhood but requires several decades to produce chronic disease. Fortunately, mosquitoes are relatively inefficient transmitters of disease. Thus short –term visitors to Haiti are unlikely to acquire this disease.

Lymphatic filariasis produces both acute and chronic clinical disease. The acute phase consists of recurrent bouts of fever with or without painful lymphadenopathy (swollen glands). The groin is the most common site for lymphadenopathy. Inflammation sometimes spreads away from the inflamed glands to mimic infection. The chronic phase presents as lymphedema (swelling of a limb) or as hydroceles (the accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the scrotum.).

Lymphatic filariasis produces both acute and chronic clinical disease. The acute phase consists of recurrent bouts of fever with or without painful lymphadenopathy (swollen glands). The groin is the most common site for lymphadenopathy. Inflammation sometimes spreads away from the inflamed glands to mimic infection. The chronic phase presents as lymphedema (swelling of a limb) or as hydroceles (the accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the scrotum.).

The diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis is made by the identification of microfilariae in blood samples or by the detection of characteristic filarial proteins in the blood. Of interest, identification of microfilariae in blood samples is most likely if the blood is drawn near midnight – the feeding time of the mosquito vector.

The treatment of lymphatic filariasis in endemic areas usually consists of diethylcarbamazine (6 mg/kg) in combination with either ivermectin (150 mcg/kg) or albendazole (400 mg.) This treatment is required every 6-12 months for 5 years. By the time patients present with chronic symptoms (lymphedema or hydrocele,) medical treatment is futile as there has already been irreversible damage to the lymph vessels. Hydroceles require surgical repair. Lymphedema is treated by compression bandaging, skin hygiene and aggressive treatment of skin infections.

Strategies to prevent or eliminate this disease rely on mass drug administration to at risk populations. The goal is to reduce the level of microfilariae in the blood below that required for sustained transmission. This requires treatment for approximately 5 years – the lifespan of the adult worms.

References:

1. Beau de Rochars MV et al. Geographic distribution of lymphatic filariasis in Haiti. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004 Nov;71 (5):598-601.